One of the pioneers of the formalist mode of art, through which International Modernism made its appearance in the Dhaka scene, early 1960s, Murtaja Baseer has always been unwilling to leave coherent footprints. Following is an excerpt from a recent interview with the artist where he examines and interrogates abstraction explored by his peers and maps his own development

Mustafa Zaman: We are accustomed to look at art and artists from within the modernist framework and often times it fails us in providing a bird’s eye view, or a picture where all the nuances are present, what is your take on that?

Murtaja Baseer: I believe the origin of art can be traced back to man’s belief in magic. That was the prehistoric beginning. In that time, man would observe wild animals in order to learn how to tame them. They would draw them on the walls of caves. By doing this they would believe they had cast a spell over the wild beasts, thereby taming them. Struggle for existence is thus the origin of art. The survival instinct led to this, nothing else. Thereafter, what we observe is the flowering of art based on religion, from the early Renaissance to the period of Renaissance or even the Byzantine era.

But cave-painting is also a form of ritual art; magic was the basis of this form of art…

Cave paintings developed out of a compulsion for survival. But early Renaissance, Renaissance or even Byzantine art was not based on such a compulsion. In the latter cases, the artist would draw following the dictates of religion, as a result of which his creative freedom took a complete backseat. Art was created in accordance with the orders of the Church, the ecclesiastic class, or a private sponsor, be that a duke or a king. Artistic liberty was unheard of; so much so that if ever an artist expressed it, his work of art became socially unacceptable. When, for instance, Michelangelo did the ‘Slaves’, it remained an unfinished series owing to a total lack of enthusiasm by precisely those for whom it was intended. This is because such issues did not interest the patrons. The life and thought of the common man is not being reflected in the art of even the Renaissance. The landscape drawings of the post-Renaissance to the Romantic period (just before Realism) begin to focus on real issues by slowly forsaking religious themes. Even then however, if we are to trace the origins of art dealing purely with the subject of man, it has to go back to Realist painters like Courbet.

When you progress further, you will see a gradual withdrawal from the subject of human form; along this line, the most significant leap occurred in America. What was the reason behind Abstract Expressionism there? It was a society of lonely isolated people. Everything is mechanized. Everything is like a slot-machine – you put a dime in it and it coughs up coke or milk. A family life defined by break-ups and separations, where parents could abandon at will their children produced a kind of restlessness, a bitterness, a deep-seated grievance. This found expression in their canvases. In the riot of colours they used, and even in their bold brush strokes. Just like van Gogh. Why hadn’t others painted with such thick strokes like van Gogh had? It was because Van Gogh’s sense of disturbance, his war within, found articulation in his art, much like abstract Expressionism. This is also the era of the Beat Generation, and the works of writers like Jack Kerouac and his ‘On the Road’ are proving to be crucial influences. Simultaneously, in Europe too, an entire corpus of protest literature started to emerge to register their angst against an unchanging system. John Osborne, Lynne Reid Banks, Allan Sillitoe, John Brain and the pioneer among them, Collin Wilson – who wrote ‘The Outsider’ and ‘Necessary Doubt’ among others – were the forerunners. Osborne’s ‘Look Back in Anger’ established him and his ilk as the worthy ‘angry young men’; come as all of them did from the working class background. Whatever is happening in art right now does not belong to any ‘movement’ as such. While earlier we had ‘isms’ like Impressionism, Expressionism, Dadaism, Abstract Expressionism etc, now we don’t, because…

But, what about of the influence of Abstract Expressionism on the art of your generation. Did you find a similarly revolutionary situation here as well that may have been conducive to its proliferation?

See, what has happened now is a deviation from a belief in movements. What reigns now is individuation. An artist now portrays his own feelings, emotions and experiences. Later, a collective may be formed out of artists who share a similar sense of alienation. But this grouping, even if centered on an apparent sharing of ideas, is not based on any philosophical belief. What I believe is that in the present age, art flows in two main currents. One is that of ‘Internationalism’ that believes art to be a universal language. The other promotes ‘individual freedom’. The entire art world is guided by these two main forces – this is my belief.

But the very word ‘Internationalism’ is premised on the modernist concept of one order reigning over all other developments throughout the world. In contemporary times, especially after postcolonial and other contemporary discursive practices have thoroughly shaken the modernist position, artists simply do not believe in the existence of ‘Internationalism’. There is another word in circulation nowadays – which may be an extension to the concept of internationalism itself – which is ‘trans-nationalism’; it is predicated on the belief that there is uniqueness to every nation and their culture has always been interconnected…

No, earlier it wasn’t like this. Today’s crossovers have been made possible by the internet technology.

In the age of internet, the flow is of such a nature, that nobody can stem it.

everybody gets to know what is happening elsewhere in a matter of a second. You could well say, we are living in an era of advanced globalization. This is especially true in our country, where globalization, internet technology is forming a link with all sorts of phenomena across the world. And they have begun to believe that art is a universal language. This is leading them to neglect their own culture, heritage and values. Take for instance, the kind of abstraction that is happening in Bangladesh today – I just can’t relate to it. I can’t understand how a country like Bangladesh can produce completely abstract works. Our artists – barring a few exceptions – still live with their families; families that have their fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters etc… they are not alienated beings.

So you’re saying that social condition determines how artists devise their languages?

The reality of America – broken families, alienation etc, and the reality of Bangladesh do not match. But why does an artist like Kibria has been doing the kind of work he has been doing? My analysis is that his original home is in Birbhum, West Bengal, India. He has come to live here (following Partition), and has no family therefore. He is a complete loner, with no friends whatsoever. This is why we see that loneliness reflected in his art. He draws graveyards, why? Because his life is scattered, scarred and alienated. He has attempted to fit this world into a beautiful framework. And his pangs – mental, emotional, and physical – have been smothered by the neatness of his process. And if I were to analyze his psyche, his alienation would be the reason thereof. Let’s consider the work of Debdas Chakraborty. The reason we find a destructive element in his art just like van Gogh’s, is that he was a member of the minority community and never been at ease in the face of the majoritarianism. So, no one could stand him. Hence his anguish, his pain. I’ve seen Debdas working when I stayed with him and observed that he works with the same anger as van Gogh (as seen in the documentary on him). So now, what is the reason behind abstraction in Bangladesh? Here too there may be two reasons, and one is Internationalism…

You mean the trend that was once characterized by a global hegemony…

But the irony is that I at least will not be able to tell which form of abstract art is pure – the one of London, the one of France…The trend that occurred in America did not replicate itself anywhere else. Not in Italy. Not in France. Not even in London. Certainly not in Germany.

The Germans had a different approach to abstraction.

The Dutch did it a lot like Expressionism, if we consider Karrel Appel…

But his was a different kind of figuration… they used to call it Neo-expressionism in the 1980s.

Maybe. I will not be able to comment on these new terms. So now…

The question I have here, sir, is that, if individual creativity be the driving force for art, what is the need to follow international trends? Or, even if I internalize an international trend, I am, at the end of the day, lending to it my own stamp of creativity…

I want to know how you look at this global trend that makes everyone want to practise installation art in the name of Postmodernism. This is in reference to your concern about the practice of abstract art in our clime.

The issue of acceptance and rejection that goes on in artistic practice is important for an artist, because he is a creative individual. Once a trend becomes popular, an artist may start practising that himself. He may innovate. How does one then resolve the conflict between internationalism, trans-nationalism or whatever global trends one is attached to and the individuality one proclaims to have achieved? In truth, however, every artist is a social being, with a certain historical background and a particular social locus; and it is possible for him to transcend that location to be influenced by a new idiom. What are your observations on this subtle yet crucial difference between influence and copy?

We have to remember first and foremost that ‘Internationalism’ exists. We wear pant-suits – that is not our indigenous costume. People in my country, in Bangladesh, wear the ‘lungi’. But my country, its soil, all of them together form a character of this land. Nature influences man. My question is why my people do not practise anything other then abstraction.

There are many other movements, abstraction is only one of them.

But why not Abstract Impressionism? Or, just Impressionism…? Why not even Realism…? So, what I have observed here is that the artists are trying to be modern for the sake of it. Because, abstraction is not their goal…. Think about the social background of the person who is doing abstract art. Think about the position of his family. Explain to me how he can take to abstraction if he himself does not feel alienated. He has to be a complete outsider. Is he alone? No, he is not! He has a brother, has to think about his sister’s marriage, worry about his father’s medicines, be concerned about his mother… Is he able to imagine himself as a totally dissociated individual? In this situation, how can one express oneself through pure abstraction? I just don’t get this. The reason behind this is the ill-impact of a book on American art called ‘American art since 1945.’

When did this happen? While you were students?

Round that time…I have the book. This along with the influence of the internet has made us continually imitate. I am not against modern art. But my problem is how can you possibly create abstract art if you are not socially alienated? Like Kibria was… and the chances of his case being repeated in a hundred years are one percent. Kibria was alienated. I support his work. Because such was his life. Scattered and bruised. His only space for organizing was his canvas, where he is fitting his art within a beautiful framework. Most of his works is very dull – why is that?

Speaking comparatively, what Mohammad Kibria had been doing through his art is just the opposite. He has been beautifying, aestheticizing.

He was not just beautifying. He was creating an enchanting world. A world he does not have.

Absolutely, an enchanting world it is…

MB: His own world, which ended in rupture, is augmented through the textures he applied. He had been presenting it in an obsessive manner, by bringing it within a stipulated area, within a boundary. This was his desired life. And here he used beautiful single colours, mostly greys or other such dark shades, with a smattering of an orange or blue, maybe. These reflected his desires in life. For me, his works are perfectly in order with his life. But when others attempt the same, I don’t see similar condition for their art to become abstract.

Kibria’s take on abstraction led him to ultimately create beautiful pictures; works that are pretty to look at. But if we view the works of Jackson Pollock or other American Abstractionists and keep in mind the alienated backgrounds they belong to, we see a certain irrationality in their works. Almost like an explosion…

That is the nature of their society. Like I said before, it is a deeply alienated society, based largely on broken families…

Most of them were displaced. Mark Rothko, for instance was displaced; he wasn’t even an American, to begin with…

You know what’s funny, is that when I was touring America in 1978 on an American scholarship, Mark Rothko, Arshile Gorky and others were recognized as American artists. But when I went back in 1999, it was a different picture – when they were categorized as Russian-Americans.

Yes, Russian-American. Earlier the custom was of americanizing people and ideas…

I find it rather amusing how individual ethnicities are exhumed. Gorky is now identified as Russian-American; de Kooning is Dutch-American.

What you are saying therefore is the bringing to the table, one’s local flavour, and negating an essentialized version of what globalization should mean: A tendency to follow a single trend as being part of globalization. Just like in your time, in the 1960s, the only trend to be followed, if you were to be considered as ‘modern’, was abstraction.

But we’ve not yet had pure abstraction here!

A tendency towards hailing abstraction as ‘the’ singular global trend was more or less there. Again, when they were discussing indigenous art, there too, only a certain kind of art was being propped up as indigenous – even though indigenous art would well connote a whole lot of other things. An innovation you institute in the particular context of Dhaka will also be understood as indigenous. But for a lot of people, indigenous automatically implies the rural. What do you have to say to that?

See, I would have to agree that indigenous should imply the rural, local, folk arts. That is what is indigenous to us.

But isn’t there a scope for innovation beyond that? One that I may institute sitting in an urban space?

No! What you will then be achieving is through the lens of a modern educated man. While the other, the indigenous derives from training handed down through generations. This is not education in the strict sense, but a legacy of understanding what traditional art comprises. But when we were children, I had seen the pictures behind rickshaws.

Those are new forms of urban art…

I’m not saying that. But they were all socially conscious works. While the theme today revolves around cinema stars, earlier they were reflective of contemporary events – whether of the Second World War or the war of sixty-five…These rickshaw artists, were by far the most socially rebellious class of artists. Much like the American pop artists, they taught us to believe that even such objects as a coke bottle, a billboard, a comic book interpretation of reality could equally be objects of art.

Stationed in Dhaka one may work on the reality of the city, or try and depict the new sociopolitical developments in Bangladesh, then it is not necessary that such work would have anything to do with what is ‘rural’. Dhaka’s reality may give rise to some new languages, where there is little or no space for the rural. How would you describe the pictures of the ‘Wall’ series you did?

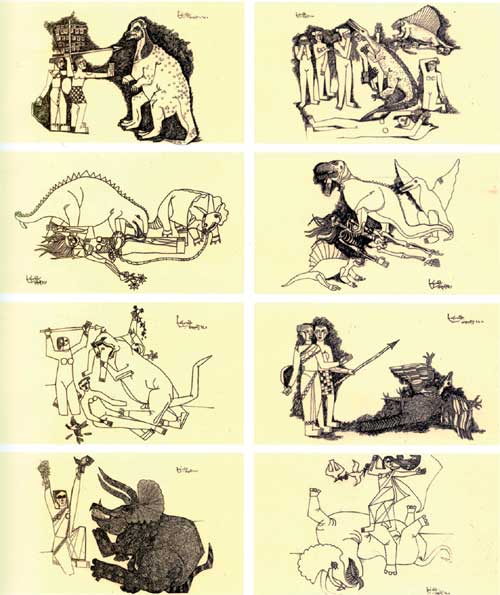

In the landscape paintings you see in Bangladesh, man is relatively less important than nature. Fields and boats find precedence over the figure of man. But my politics is based on the intrinsic relation between man and nature; nature exists because of man. Man has no relation with nature. Therefore man is bigger, and nature cannot dominate. I’ve drawn a woman with a pitcher just like many others like Quamrul bhai. But I haven’t depicted her like a beautiful lady; instead, I’ve shown how carrying a heavy pitcher everyday in the same position has scarred her body, how it has led her to bend. I’ve felt the physical pain of a girl who goes to the river to fetch water and have tried to portray that. I’ve interpreted this in my own way, not from the point of view of a foreign tourist.

I was deeply inspired by the works of Paritosh Sen when I went to Italy. This was the time when he had returned from Paris. ‘The Statesman’ carried weekly articles on these Paris-returned artists back then. Others who were featured were S M Souza, Akbar Padamsee, and Ram Kumar among others. Raza was still in Paris. I went to study in Calcutta in 1954 and met Paritosh Sen in 1955. I was, by then working with palette knife. But I wasn’t being able to draw lines sharp enough; they would break. This is when Paritosh Sen helped me. I shared this new learning with Kibria. The architect Jalaluddin saw my work at Karachi after I returned from Italy, and commented that my line treatments were like Kibria’s. I was aghast! I was the one who had taught him the technique! I stopped working with palette knife to draw lines from then on, and haven’t returned to it ever since.

The work of almost everyone was similar at that time, in terms of the treatment of line and the organizing principle applied to the picture plain…

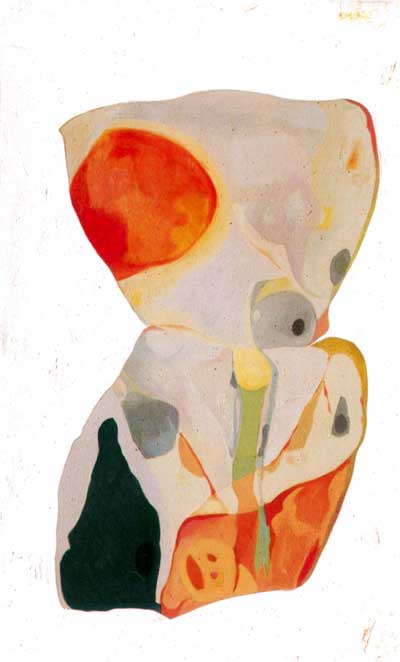

I introduced this particular way of treating lines in Dhaka, having learnt it from Paritosh Sen. I exhibited my ‘Waiting for Tomorrow’ and other works in 1956. And it was evident to all who saw that it was me who was using lines like that for the first time. This influenced Kibria, and Shahtab, in turn. I had already left for Italy by then, and had started depicting ordinary people. The exhibition I had in Karachi on my return after two years, focused on my depictions of these ordinary people; filled as I was with nostalgic yearning for home. I began painting Bengali women. When I went to Lahore thereafter, I went through another transformation. Grey became a favourite colour. Earlier my works would be pre-planned. I would first draft a sketch, make a first drawing, I would write and jot down colours marking them with ‘B’ for blue and ‘R+B’ for red. I would plan layerings by denoting which colour would come at the base and which would follow. But the works in Lahore flowed without any planning. I drew on the canvas placing it on the floor; without any easel. And colours were liquid, enamel or lacquer – and a few oils. I would apply colour with my fingers, scratching the surface of the canvas. I didn’t know myself what I was doing. I used a very tranquil shade of white and smudged it with cloth and created a textured surface. I drew lines over it with a mill and saw an image emerging.

And this later tendency swerved towards abstraction…

You could say that. Then I got married in 1962. I was not used to a nice disciplined life. So I started working with geometric patterns. I started feeling that everything is interrelated – trees, hens, animals, man – are all bound within the single framework of a common architect. There is an inherent interlink.

The works that were executed using broad lines…

I tried to show that everything fundamentally belongs to the same structure. Placed within one particular architectural structure, none of them are isolated from the other. A house, a hen, a man are all unified. My contemporaries in the sixties, like Aminul or Kibria were working along the grain of pure abstraction. And I started feeling like an outdated misfit – not quite modern. Because, modernism back then equaled abstraction. And this belief still somehow holds ground here.

My ‘Wall’, or ‘Eruption’ or ‘Radiant’ and even ‘Wing’ series has all seen me reject the kind of abstract beauty many cultivated. And this forms the crux of my aesthetics

Article link: https://departmag.com/index.php/en/detail/185/Re-situating-Modernism-and-A-conversation-with-Murtaja-Baseer