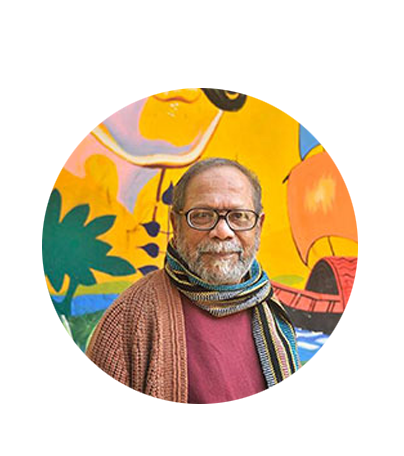

On the occasion of Murtaja Baseer’s 80th birthday, Prothom Alo published an interview of the artist on 12 August 2011. The interview has been reproduced here in his memory.

Why do you paint? When did you start painting? What do you want to express?

“I don’t want to answer such questions anymore. How many times will I repeat the same things?”

Actually the artist Murtaja Baseer, who was going to be 80 on 17 August, didn’t dwell on such things in the interview. The conversation revolved more around immortality, living beyond death.

Around 30 years ago, the famous historian and professor at Dhaka University ABM Habibullah had passed away. His obituary, as far as I recall, appeared in a small column in the inside pages of the Observer. I didn’t find the news in any other newspaper. I was pained. Such a renowned scholar had passed away, yet there was not mention of it anywhere! I lived in Chittagong at the time. I went to a few newspaper offices and asked my acquaintances, ‘Where will you place the news when I die?’

“What are you talking about, Baseer bhai!”

“No, tell me, I need to know.”

Some said, in the inside pages, some said on the back page. It was possibly Dainik Bangla that said they would make it a front page, single column report. The editor of that newspaper was my friend, poet Shamsur Rahman. Maybe that’s why they had said they would give me that space.

I pointed to the headlines and asked, “Won’t you place it here?”

They looked at me and said, “What are you saying, Baseer bhai!”

I said, “That means I will have to live for as long as my death doesn’t make the lead news. I have to prepare myself accordingly.”

That was Murtaja Baseer speaking. He will be 80 on 17 August, this man who always thinks of himself as a 30-year-old youth. Old age doesn’t touch him. He wants to live on in this works. He wants immortality. I ask, how far have your preparations for this proceeded?

It’s not easy making it to the first lead. After their deaths, my father Dr Muhammad Shahidullah and my friend Shamsur Rahman made the first lead by their merit. I can’t go outside of my talent. It was around four or five years ago when a famous artist of this country told me, “Your paintings are nothing.”

I asked him, “Do you think my work is hurried? That I lack dedication?”

The artist replied, “No, you have complete dedication and integrity.”

“Then what? I put myself completely out there. I don’t create stunts. I can’t go beyond whatever talent I have.”

Murtaja Baseer paused and continued, “I have to admit though, I am a controversial artist.”

You say that yourself?

“Yes and for a reason. I go ahead of time. When I worked with transparency, people didn’t understand. Even when I worked on my ‘Wall’ (‘Deyal’) series, I was questioned. After independence when I did the ‘Epitaph for Martyrs’, I heard remarks like, Baseer copied from an anatomy book. Many people took my paintings down because I won the Shilpakala Academy award then. But are those paintings with me now? Not a single one. People come to me asking if I have paintings of my ‘Wall’ series of the ‘Epitaph’ series. I never paint with buyers in mind and that is why I am not a popular artist. I just paint whatever comes to my mind. But the general people in our country didn’t understand art, and they still don’t. There is nothing wrong in that. For example, when I went to Lawrence Garden in Lahore and listened to Raushan Ara’s classical songs, I left after a while. I wasn’t quite prepared to listen to classical music, to take it in.”

Our discussion is about immortality. Murtaja Baseer, the son of Dr Muhammad Shahidullah, held an exhibition to celebrate his parents’ 100th wedding anniversary. Dr Muhammad Shahidullah still lives on. How do you feel about this immortality?

“Dr Muhammad Shahidullah is not living on because of his offspring or heirs. Their attraction was for his property.”

Can I write this?

“Why not? When Shahidullah died, I, Murtaja Baseer, filed a case for his property because no one was giving me anything. It is not just Dr Muhammad Shahidullah. Justice Shahabuddin Ahmad once told me, Hamidul Huq Chowdhury’s children also filed cases after his death. It is unfortunate. A father had so many dreams for his children before they are even born, he rears them and educates them and then the moment he dies, the children are in a scurry to replace his name with theirs as owners of his property. Yes, I too filed a case for my fair share. Dr Shahidullah’s children did not make him immortal. Shahidullah’s work has immortalised him. I question myself, what have we done for him? Before children would read about his life in their schoolbooks, but not anymore. We haven’t let the younger generation know about him. How many people turn up to attend his memorial at Bangla Academy?”

“Let me recount an interesting anecdote. A few days before Dr Muhammad Shahidullah died, journalist Hedayet Hossain published his interview in Dainik Pakistan. The man who had devoted his life to the Bangla language, who spoke about the language at a discussion presided over by Rabindranath at Shanti Niketan, said in clear English, ‘I will be forgotten very soon.’”

“A road had perfunctorily been named after Shahidullah in Dhaka, though there is no mention of it anywhere. Yet in West Bengal there is an entire road in Barasat, a college at Chandraketu Garh in the village Piyara and a ferry that crosses the river Ichhamati named after him. A bridge has even been named after him. Just as people live on in their work, people must also learn to respect them.”

You want to live on in your works. Those who live in their works are not ordinary people. They are famous. Why did you want to become famous?

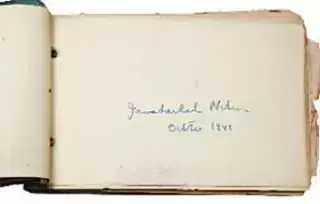

“My father was the principal of Azizul Huq College in Bogra. I was very unruly and my father would always be receiving complaints about me. One day he called me and said, ‘either become famous or notorious. Don’t be mediocre.’ I decided to be famous. By then I learnt about who were famous. When I was a student of Class 10, I drew a picture of Jawaharlal Nehru on a page from my father’s Remington Bond pad and sent it to Nehru. I wrote, I am a student of Class 10. I have drawn your portrait and sent it to you. I want your autograph in exchange. He sent me his autograph, dated September 1948.”

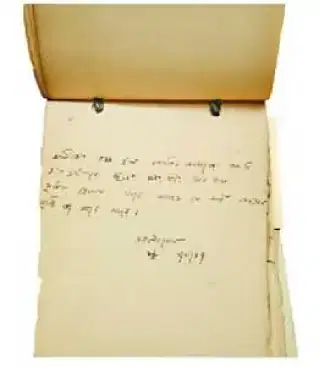

“I had read a book about the looting of the armory in Chittagong. I leant about Surja Sen’s companion Ambika Chakrabarty. I have her autograph and picture too. Communist leader Bhabani Sen wrote to me about the responsibility of an artist. I also knew about the first Bengali to travel the world by cycle, Ramnath Biswas, or the philosopher Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan. At the age that I read about these people, learnt about them or even came into contact with them, many at that age hadn’t even heard about them. “

“When I was in Paris, I would sit in Marmottan and be so excited about Jean-Paul Sartre. Existentialism had taken over my existence at the time. But my fellow students from other countries were not so enthusiastic. They said time had gone ahead of Sartre. The day Picasso died, I thought everything would shut down for the day. I had no money so I could do some window shopping. But everything was going on as normal. One of my friends teased me, your grandpa had died. So I know what it means to be famous.”

When I turned up at 12 in the afternoon of 3 August at Murtaja Baseer’s house in Manipuripara, I saw a stamp album on top of a pile of books. He was reading about certain rare Russian stamps. When I handed him two coins I recently got from Bhutan, he laughed happily like a child, “I have currency notes from Bhutan in my collection, no coins.” I asked, you are still so passionate about stamps and coins, you hunt for them all over. Why have you stopped collecting autographs?

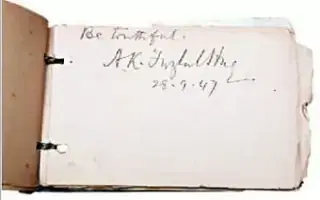

He turned the pages of his autograph book, pointing to the autographs of Ustad Alauddin Khan, Kashmir leader Sheikh Abdullah and many other rare autographs. He said, “Sher-e-Bangla AK Fazlul Huq went to Bogra. I took his autograph. I said, write something and he wrote, ‘Be truthful.’ That’s when my interest in autographs waned. He told so many lies all his life and he wrote ‘be truthful’ to me?”

Murtaja Baseer enjoys solitude. He does not enjoy crowds, hustle bustle and such. He spends time in his verandah, watching coconut trees, the rustling leaves, the woodpecker pecking away. When he was in Chittagong and his wife and children would come to Dhaka, he was quite happy sitting alone in his chair at the dining table. I asked, your life is very organised and disciplined now, but at one time it was your rule to break rules. Why?

In his novel ‘Old Man and the Sea’, Ernest Hemingway said a man can be destroyed, but not defeated. I believe the opposite, a man can be defeated, but not destroyed.

“When I broke rules, I was breaking conventions. Now it is time for me to sit still. But from my childhood I would feel no one in the family loved me or wanted me.”

But your mother suffered immensely in giving birth to you.

“That is true. My mother would always say, ‘You made me suffer before you were born and still make me suffer.’ Many people asked my father about having so many children. He would say, who is to say the last one won’t be a genius? Annadashankar mentioned this about Dr Muhammad Shahidullah in one of his writings.”

“I once ran away from home when I was in Class 7. Again, when I was in Class 10 I went to Lucknow. Then I got homesick and returned. I had an ego, an attitude. I had many brothers and sisters. Say if my mother made some firni (rice pudding) and placed it in bowls on the table and I found there was one less bowl, I would immediately imagine I was the one left out. Maybe it was a psychological problem, but I would feel unwanted. From my childhood I was a loner. But now I am really alone. My four close friends – poet Shamsur Rahman, dramatist Sayeed Ahmed, artist Debdas Chakraborty and artist Aminul Islam – have all passed away one by one. I have no one to talk to now. I am really all alone.”

You advise your junior artists not to get lost in fame and fortune. You say that fame and fortune is a slippery path and you wear rubber sandals. If you are not careful, you will slip and fall. Why do you say this?

“It was the late Fazle Lohani who had once told me this. He said this seeing my attitude. I now repeat this to the next generation. That lesson freed me from being lured in by fame and fortune. I learnt many things from many people throughout my life and changed myself.”

“In Lahore in 1961 I asked Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Faiz bhai, why am I not famous? He said, Baseer, do not run after fame, fame will run after you. That too was a lesson for me.”

There is a photograph on the wall of young Murtaja Baseer with Zainul Abedin. It was taken by the artist Kamrul Hasan in hospital, 20 days before Zainul Abedin died. Murtaja Baseer looked at the picture and said, “I hurt Zainul Abedin with my attitude too. But he told me, ‘You do good work, but you are not the only one who does good work. We draw too.’ He told me to build myself up in a way I could laugh both at praise and at criticism. He said that because of my attitude. It took me 10 years to actually internalize those words. Now I laugh when I am praised and laugh when I am criticised.”

We began with immortality. Let’s end with immortality too. What would you like to say?

“I dreamt about being immortal from Class 10. I studied at the Coronation Institute in Bogra at the time. I went to my friend’s house one morning and saw him going out with a gamchha (cotton scarf-like towel) around his neck. ‘Where are you off to?’ I asked.”

“He said, ‘I’ll be back in half an hour, I’m going for a dip in the river.’”

“I came back after half an hour to see a crowd in front of his house. I pushed through the crowd to see my friend lying there on the ground.”

What happened?

“I heard that my friend drowned in the river Korotoa. That hit me hard. I had always heard that man is mortal, but then that day I thought, man in immortal. I must be immortal. I must achieve something in life that I can live beyond death But how? That is when I started drawing, writing. I wanted to live on in my creative works. Sometimes I think, I will live perhaps not in my paintings, but in my research on the Habsi Sultan of Bengal or the terracotta of West Bengal’s temples. Who knows? Time will tell. In his novel ‘Old Man and the Sea’, Ernest Hemingway said a man can be destroyed, but not defeated. I believe the opposite, a man can be defeated, but not destroyed.”

This interview appeared in the print and online editions of Prothom Alo and has been rewritten in English by Ayesha Kabir